Last week, a Saint Jerome boy, who coolly described how

he beat a classmate to death with a baseball bat, was described

by psychiatric experts as not responsible because he suffers

from a paranoid delusionary disorder. And in another Canadian

courtroom, an accused sex-killer was portrayed as a case of

multiple personality disorder. While prosecutors and the occasional

skeptic may express disbelief, the courts have become so accustomed

to listening to psychiatrists explain away hideous crimes,

these arguments often sway judges and juries.

When Rita Graveline shot her husband in the back while he

slept, psychiatrists testified she was the victim of "battered

wife syndrome" which had caused a momentary loss of consciousness

or "dissociative amnesia." When Andrew Leyshon-Hughes

thrust a carving knife 21 times into sleeping Nancy Eaton

and then raped her dying body, psychiatrists rooted back through

his history, found that he was a "blue baby" and

declared the cause to be his "crocodile brain."

Psychiatry has a long and winding history of describing criminal

behaviour in pseudo-medical terms. Since well before the 1978

"Twinkie" defense rationalized two cold-blooded

murders as temporary insanity due to the effects of eating

too much sugar, we've been swallowing this junk.

These days, there are very few cases in which psychiatrists

don't try to shift the focus from the facts of the crime to

the mind of the criminal. They were hard pressed to fit a

label to Paul Bernardo. And they had trouble finding anything

to say about Harold Shipman, the British physician who murdered

more than 150 patients. Some crimes, it seems, do still defy

explanation.

This situation, however, is about to change. At last month's

annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in

New Orleans, Michael Welner, a clinical associate professor

of psychiatry at New York University School of Medicine, proposed

that the time has come for psychiatrists to assume responsibility

to detect evil. This would be an about-face for a profession

that has, for more than two centuries, been telling the courts

that vile and brutal acts are symptoms of mental diseases.

It wasn't long ago that psychologist Judith Becker, president

of the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers, stretched

our imagination when she diagnosed the mass-murderer Jeffrey

Dahlmer as suffering from "cannibalistic compulsions."

She even went so far as to suggest his problems might "have

been alleviated had he felt safe to seek help when his deviant

fantasies began in adolescence."

But Welner isn't interested in finding a cure. Instead of

offering to help the accused, he intends to help society uncover

the evil in our midst. Relying on language of a bygone moral

era, he would prefer to consider those like Dahlmer so depraved

and evil as to be beyond help -- and beyond mercy. And he

is offering his expertise not only to criminal courts but

also to family, civil, human rights and military courts. He

is prepared to expose "evil acts of evil parents"

and the wickedness in employees that causes disputes and disruptions

in the workplace. To lend an air of scientific credibility

to these value judgments, he has created a "Depravity

Scale," a measure that he claims will identify "evil

behaviours for the courts."

From time to time other psychiatrists, such as Scott Peck,

have talked about evil, but Welner is the first to make a

serious effort to sell the skill of detecting it. And what

makes his initiative particularly frightening is that he is

doing so at a time when the soil is ripe. Crime victims are

outraged when the punishment seems not to fit the crime. Words

like "monster" are being used to describe hunted

criminals and society is caught up in a fearful urge to rid

itself of violence.

I can understand the desire to distinguish Good and Evil.

And I think that long ago we should have cast aside the foolish

notion that evil acts are a sign of sickness. But I am not

willing to entrust the profession that brought us the Twinkie

defence and "crocodile brain" to tell us who is

"evil." I imagine, with dread, how far they might

take this power.

Until now, psychiatrists have remained within the bounds of

their medical profession. Whether we have believed them or

not, they have interpreted criminal behaviour in terms of

health and disease. Sometimes the illnesses, such as multiple

personality disorder or temporary insanity, were considered

curable. At other times, when diagnoses such as psychopathy

and pedophilia were used, the conditions were deemed less

amenable to treatment. However, whatever they did, like it

or not, they stayed within the domain of medicine.

In identifying evil, they are crossing the line into the practice

of religion, for "evil" is not an illness but rather

a moral state. Determining who is evil is a religious, not

a medical, act. By performing it, psychiatrists will become

the inquisitors of the 21st century.

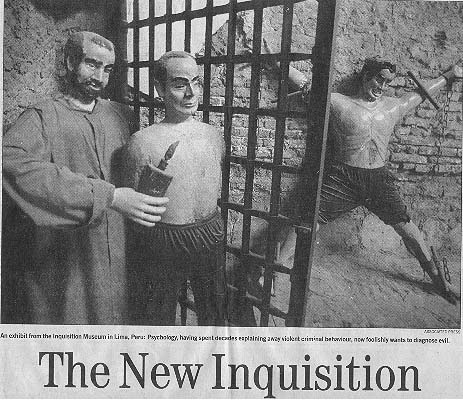

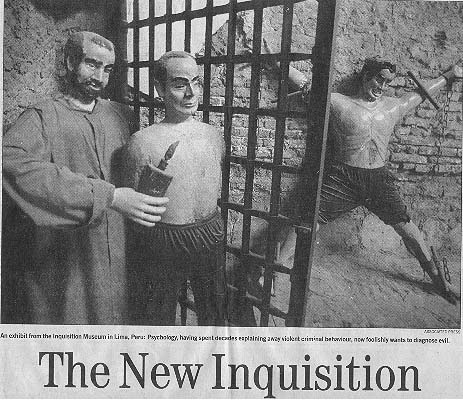

In Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries, and later in

North America, inquisitors traveled the country hunting out

evil using the Malleus Maleficarum, the famous manual

for witch-hunters, as their guide. Serving as the expert witnesses

at the witch trials, they distinguished diseases due to natural

causes from those caused by demons.

If Welner's idea takes hold, these inquisitors could rise

again, disguised as psychiatrists and using the Depravity

Scale as their guide.