Losing our innocence;

A televised execution would not be sweet "revenge"

June 11, 2001

|

|

|

Conspiracy or not, a judge ruled last week that Timothy McVeigh would die by lethal injection today. As the assistant police chief in Terre Haute, Indiana, said, 'We're in execution mode again." This is the first U.S. federal execution since 1963 and,

to borrow a vaudevillian phrase, "What an execution it

will be!" Banking that no higher court would halt it,

hucksters scrambled to reassemble their wares - buttons and

other trinkets to be flogged and new T-shirts to be printed.

The T-shirt, which earlier bore a picture of a syringe and

the words: "Hoosier Hospitality. McVeigh / Terre Haute

/ May 16, 2001, Final Justice," features a new date.

Computer hackers frantically sought ways to access the closed-circuit

broadcast of the killing, set up for survivors of the Oklahoma

bombing and relatives of those who died. Grocers in the quiet

Midwest town placed fresh orders for sandwiches to feed the

anticipated crowd. Officials designated two parks for expected

protesters: One for those applauding the execution and the

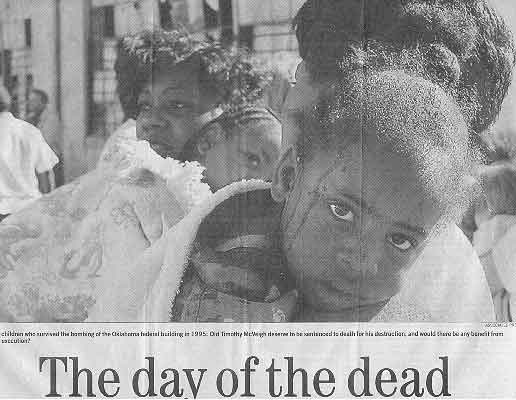

other, a few blocks away, for those opposing it. McVeigh's was a heinous crime that left 168 dead, including

19 children he dismissed as "collateral damage."

Those who survived talk of limbs chopped off and other horrors;

while those severely brain injured still lie helpless, unable

even to tell their stories. This is victim impact of such

a magnitude that the most severe punishment is clearly, unarguably

justified. That's what has made the controversy about the nature of

McVeigh's punishment, along with the hullabaloo over who should

be allowed to watch, so intriguing. Many of the survivors,

victims' relatives and friends and those declared "secondary

victims" petitioned U.S. Attorney General John Ashcroft

for their right to witness the execution. Having been thoroughly

immersed in the doctrine of the grief counsellors who have

swarmed around Oklahoma City since the explosion five years

ago, they contended that only by watching could they achieve

healing of their emotional pain. Ashcroft, having accepted the popular notion of finding "closure,"

agreed to provide a private screening to this select audience.

Unhappy with this limitation, Entertainment Network sought

court permission to publicly broadcast the execution, but

the request was turned down. So, the public must rely on hackers. Why is there all this interest in watching a man be put

to death? How can it benefit anyone? For the survivors and

relatives, what can it accomplish? While "closure" may be their announced motive,

the private reason, I suspect, is raw vengeance. And, while

Homer wrote that vengeance is "sweeter than honey,"

I doubt that will be in this case. What would they feel if,

as he is still very likely to do, McVeigh claims "victory

at 168 to 1," and quotes Henley's powerful lines: "I

am the master of my fate, I am the captain of my soul"?

Would they be satisfied to watch him then drift into a tidy,

bloodless death? The experience might very well turn out too

bitter to swallow. And what about the rest of us? What would we get out of watching? Likely, the answer depends on where we stand on the death penalty and on our attitude about victim rights. During McVeigh's trial, many of the victims, understandably, felt he should pay with his life. During the sentencing phase, a Time/ CNN poll indicated that 78 per cent of Americans thought he should die. On the first day, when a honk in front of the courthouse was meant to signal that he should "fry," more than 24,000 citizens honked their horns. One man even displayed a billboard carrying a caricature of McVeigh with dynamite sticks wedged into his ears and mouth, hands holding lit matches and the caption: "Let Us Have Him." With this thirst for a lynching, McVeigh's quiet execution

is unlikely to be quenching. Decapitation, hanging, even the

old electric chair would, I reckon, be more satisfying for

those who cry for blood. But people such as Bud Welch, who,

though his daughter died in the bombing, opposes the death

penalty, are likely to react quite differently. Welch admits

that initially he had a strong urge for retribution, but then

realized that killing McVeigh would bring no emotional relief. Having met with McVeigh's father, he thinks that killing another man's child is wrong, no matter what. And even before the death sentence was rendered, Archbishop Charles Chaput was trying to get this point across. "Killing the guilty is wrong ... while it may satisfy society's anger for a while, it cannot release the murder victim's loved ones from their sorrow." Perhaps we should not only be allowed, but required, to watch the execution. Whether it heals or hurts, satisfies or sickens, we ought to witness this extreme act of the state on behalf of its citizens, for then we would have knowledge of what we speak. Jim Willett has done just that. As the warden at Huntsville Prison, he is the overseer of all Texas executions. Last year, he witnessed 50. In an interview with National Public Radio, he revealed that "there are times when I'm standing there, watching those fluids start to flow, wondering if what we are doing is right. It's something I'll think about for the rest of my life." If we were all obliged to watch McVeigh's execution, we might

find ourselves also asking if it is "right." But

in this era in which personal feelings so often have primacy

over moral principles, it seems disturbingly possible that

the question would be swept aside by the cry for blood. |

tanadineen.com

@ Dr.Tana

Dineen

1998-2003

by

Dr. Tana Dineen, special columnist,

The Ottawa Citizen