The pursuit of happiness

Sep. 23, 1999

|

||

|

'Ask yourself whether you are happy," wrote John Stuart Mill in his 1873 Autobiography, "and you cease to be so." If Mill was alive today I suspect that he might go on to say: "Ask yourself whether you are depressed, and you will surely find some reason to be so." While the elusive experience

of happiness might be compared to a butterfly which, if pursued,

always eludes your grasp; depression, once you begin to think

about it, may well land upon you with a thud. Depression has

become a medical term so broadly applied now that any absence

of personal happiness, of inner contentment or of material

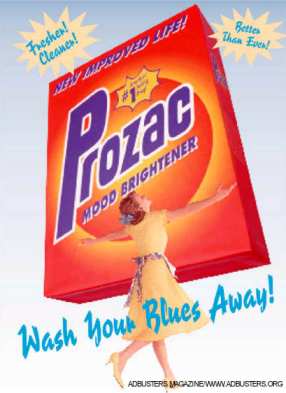

comfort can easily be translated into the illness. Now, I don't wish to imply that depression is a word that should be removed from our lexicon. But I would point out that it is being reshaped, stretched and over used to the extent that a whole array of emotions are in danger of being obliterated. Linguistic precision is giving way to psycho-speak as sadness, "the blues," "feeling down," and "low spirits" are now all clumped under the rubric of this clinical term, depression. By sleight-of-word, our personal feelings are being transformed into mental health problems suited to the diagnostic whims and treatment offerings of therapists. Consider the upcoming National Depression Screening Day, October 7, sponsored throughout Canada and the U.S. by mental health groups, modeled on similar medical screening days for high blood pressure and glaucoma. The expressed purpose is to educate the public about the dangers of depression - to whit, it offers a free screening test to help people find out if they are depressed and need treatment. But why wait until Oct. 7? Screening tests are readily available anytime on the Internet. One from the New York University's Department of Psychiatry, for instance, asks 10 questions and gives instant results. The questions include: "Do you feel sad, blue, unhappy or 'down in the dumps'?; Do you feel tired, having little energy, unable to concentrate?; Do you feel uneasy, restless or irritable?" and "Do you have trouble sleeping or eating (too little or too much)? for more than two weeks." People rate their answers on a five-point scale from "Never" (scoring 0) to "Most of the time" (scoring four). I gave it a try recently, checking "Most of the time" for two of the items and "Never" for the remaining eight questions. A click of my mouse and back came the response: "Your answers reflect the presence of depressive symptoms. It is advised to seek a psychiatric consultation. Ask us for Referral Information." Several other combinations yielded the same reply, leaving me wondering whether tests like this uncover actual depression or plant the suggestion that one is depressed. Could it be that their purpose is to open the door to psychological treatment? When that door is opened, it seems that the most likely treatment, other than the ever-popular Prozac, is cognitive behaviour therapy which assumes that depressed feelings and behaviours are a result of negative thoughts and self-defeating beliefs. Therapists reason that if people learn to understand and change their thought and beliefs, depression can be reduced. But what if the screening tests are responsible for creating the depressive thinking? Perhaps through the screening, some people may actually be led to see themselves as depressed so that therapists, through treatment, can then help them to stop thinking of themselves as depressed. The American psychiatrist, Jerome Frank, states the point well. In Persuasion and Healing, his classic text on psychotherapy, he writes that "ironically, mental health education, which aims to teach people how to cope more effectively with life, has instead increased the demand for psychotherapeutic help. By calling attention to symptoms they might otherwise ignore and by labeling those symptoms as signs of neurosis (and depression), mental health education can create unwarranted anxieties, leading those to seek psychotherapy who do not need it." For a long time, questionnaires have been recognized as effective marketing tools. It could well be that the mental health industry has caught on to this sales approach and is profiting from encouraging people to ask the question "Am I depressed?" Perhaps most of us would be better off if we ignored the question and focused instead on dealing with the woes which most of us are resilient enough to overcome in time. So, beware the entrepreneur in helpers clothing. |

tanadineen.com

@ Dr.Tana

Dineen

1998-2003

by

Dr. Tana Dineen, special columnist,

The Ottawa Citizen