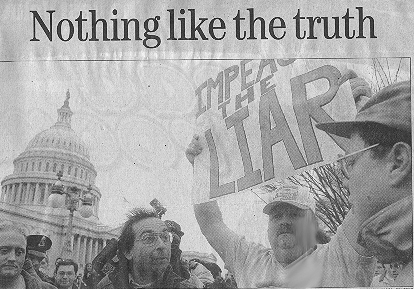

Nothing like the truth:

Even judges are excusing lies in our courtrooms, which undermines

the entire legal process.

While

the rhetoric of "good versus evil" gets a lot of play these

days, "truth-telling" has fallen off the virtues scorecard.

While

the rhetoric of "good versus evil" gets a lot of play these

days, "truth-telling" has fallen off the virtues scorecard.

Lying, it seems, has acquired a moral status all its own. We accept it as a political necessity, a form of politeness, a social convenience, even an expression of sensitivity and kindness.

But while wilful deception has become a part of our day-to-day life,

we still cling to the belief that one place remains a bastion of truth.

Just as God is to be found in churches and money in banks, we expect

truth to be found in the halls of justice. After all, witnesses swear

an oath to "tell the truth ... and nothing but the truth"

and perjury is a crime. A couple of recent cases that sparked public

notoriety were that of Jeffrey Archer, the former British MP and novelist

currently appealing his four-year sentence for perjury and,

of course, former U.S. president Bill Clinton, who came perilously close

to being charged during the Monica shemozzle.

But those are the celebrity cases. What about all the rest?

Too often, I hear of people lying to police, judges and juries and

I wonder why it is that almost all of them get off scot-free. It's due,

in part, to our tendency to use other words to obfuscate the deed. "It

is not a lie," exclaimed Alexander Haig, president Ronald Reagan's

secretary of state, "it's a terminological inexactitude!"

Lies these days are usually disguised as false accusations, misperceptions or emotional misstatements and talked about in linguistically misleading terms for which the courts have developed an unhealthy tolerance.

Take, for example, the recent case in which a 17-year-old Hamilton woman claimed that, while walking through a park, she was attacked by a man who dragged her toward some trees and sexually assaulted her. Providing a description of her attacker, police searched the area for evidence and appealed for public assistance. Their hotline was swamped with tips before the teenager admitted she'd made up the story. The complainant's expression of remorse persuaded police to overlook her lying; so, she wasn't charged for giving a "false report."

A decade ago, a similar fabricated story, resulting in a police investigation costing $300,000 and the arrest of an innocent man, did prompt the Toronto police to lay charges of public mischief. But, when the case went to trial, the judge, fully aware of the blatant lies and their impact, acquitted the woman because he thought she might have been "suffering from some sort of stress disorder."

It seems that we've reached the point of viewing lying to be, if not a sickness, then, a natural trait. "Lying under oath," says Judge Roderic Duncan, of the Alameda County Superior Court, "is an accepted element of most trials." He describes an occasion when he reported "a slam-dunk case of perjury" to the local prosecutor, pointing out in a letter that "one of the parties admitted in my court that he had lied under oath." The district attorney shrugged his shoulders, never bothering to respond.

Lying under oath is just something everybody does -- even the police who whimsically call it "testilying." The celebrated trial of O. J. Simpson provided us with a couple of pristine examples of perjured police testimony by detectives Mark Fuhrman and Philip Vannatter who, in Judge Lance Ito's words, had demonstrated a "reckless disregard for the truth." We live in an era when even the most flagrant disregard brings little more than harsh words from judges.

Last April, Nancy Jean Strobel admitted that she had committed spiteful perjury in sworn statements both in Canada and in Hawaii. B.C. Supreme Court Justice Robert Edwards told her that she was flagrantly in contempt of court orders allowing her ex-husband to visit his children and that her behaviour warranted "a substantial jail sentence" -- but he let her off. Why? Because, in his mind, it was more important to keep an angry mother out of jail than to teach her, and her five-year-old daughter, the value of truth.

Another exposed liar, Cathy Fordham of Ottawa, has left a trail of an estimated 55 complaints with the police, seven reportedly involving grievous claims of sexual assault. One man, Jamie Nelson, spent more than three years in prison before her lies were uncovered and he was acquitted. When Ms. Fordham was convicted two years ago of public mischief and given a paltry six- month sentence to be served in the community, she said she just wanted to "put it all behind her." But she didn't. The meagre penalty had no effect, so this month she'll be sentenced again in an Ottawa court, this time for uttering death threats against another man she had falsely accused. Perhaps now she'll get more than a slap on the wrist.

So what's the big deal if lying happens all of the time with little, if any consequence, to the liars?

I admit to my share of lies -- I'll say I'm busy to avoid a meeting

or thank someone for a lovely gift when, really, I hate it. But I can

distinguish the extremes of deception and separate the grey lies (there

are no white ones) from the black lies. I find comfort in the

belief that we live in a society where malicious lies are frowned upon.

But, when our courts tolerate even the blackest of lies, we risk losing not only any sense that their verdicts are based on truth, but also our faith in the moral principle of truth itself. If our courts show a disregard for veracity, then how is it possible for us to assume that anyone really cares about truth-telling?

If we can't trust our courts to uphold the principle of truth-telling, then who can we trust?

For printable copy, Click

Here

tanadineen.com

@ Dr.Tana

Dineen

1998-2007

by

Dr. Tana Dineen, special columnist,