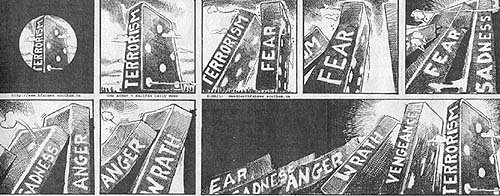

Losing our innocence:

A continent grows up the hardest way

Sept. 14, 2001

|

|

|

The

United States had its ego shattered, for better and for worse.

When my clock radio woke me to the news of the terrorist attacks

in New York and Washington, I felt the world had changed forever.

Surely, as Americans and Canadians, we could no longer lull

ourselves into a false sense of safety, order and peace. In

all the years I can remember, we have, like children, assumed

that nothing could hurt us, that within our borders we were

not only invulnerable but also immortal.

Yes,

there had been a few acts of terrorism; the FLQ in Quebec,

the previous attack on the World Trade Center and the Oklahoma

bombing, but these attacks seem relatively minor when compared

with this week's violence. Then, we were able to clean up

the debris, shed our tears, erect monuments to the victims,

and punish the perpetrators. Things could revert to the way

they were and we could go about our days believing we had

a firm grip on peace. As North

Americans, we have languished far too long in a naïve,

childish belief in our security. Like spoiled children, we

have basked in the delusion that we were better than others,

that we had all of the answers. We've felt entitled to tell

other countries how to handle their problems. With our vision

of a new world order, we've sought to spread a "culture

of peace" around the globe, offering up our plans, ignoring

the failures. The terrorist

attacks this week ended our childhood. They cracked the façade

of security and jolted us out of any illusion of superiority

and invincibility. We have joined the rest of the world, one

that already knows the effects of terrorism and how to live

in a less than peaceful world. While

the events were shocking -- and the mounting death toll will

be, in the words of New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, "more

than any of us can bear" -- what happened is not that

different from what is experienced in other parts of the world;

the IRA threat in England, the Basque violence in Spain, the

Israeli and Palestinian conflict in the Middle East, and so

on. In Peru, it's the Sandero Luminosa. I was in Lima once

on New Year's when, at midnight, just to remind everyone of

their destructive power, these anarchists blew up the power

lines and blackened the capitol. In Britain,

I have a physician friend who tries to deny the threat of

the IRA. He doesn't talk about it, but everyone knows he avoids

using the Underground for fear of a bombing. I keep in touch

with a psychiatric colleague in Israel. When I first met him,

he was arrogantly confident; when his neighbour was killed

by an Iraqi Scud missile, I saw him become a broken and humbled

man. People

who live with the constant threat of danger are forced to

let go of the notions that make us less than human. In most

parts of the world, people learn to live with the on-going

threat of danger. Children see people die. They lose their

innocence. They know that life isn't fair, that good people

die, bad people can survive and that war and peace are two

sides of the same coin. People

who live with terror are more wary and less secure and, at

the same time, they're often more human. While they may be

permanently scarred, they exhibit strength and resilience.

And they value life differently. Today,

as rescuers sort through the debris, it is difficult to imagine

that anything good can come out of such tragedy. It is hard

to ponder anything beyond revenge. But none of us can go back

to life as usual. The time has come to let go of the hopes

and dreams of our lost adolescence. We must come to terms

with the fact that life is not always about healing. Life leaves scars. When, as nations and as individuals, we accept them, we will have grown up -- like it or not.

|

tanadineen.com

@ Dr.Tana

Dineen

1998-2007

by

Dr. Tana Dineen, special columnist,